1.1 State of kelp restoration and guidebook motivation

Kelp forest restoration or enhancement has occurred in some form since at least the 1700s in Japan, and more regularly since the 1950s elsewhere in the world. The field is now truly global, with projects in at least 16 countries and multiple languages as of 2021 1. Across these projects, the approaches to restoring kelp forests are truly varied, with many different methods tried and tested. Restoring kelp forests and the services they provide to coastal communities is a societal challenge, and a diversity of groups from universities, governments, local communities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and businesses have led projects.

Motivations for restoration differ among projects, but the desire to reinstate healthy productive kelp forests remains a common unifier across time and localities. Despite such a rich and potentially informative history, projects have often remained disconnected, and there has been little communication between practitioners from different regions. Many of the previous lessons learned about restoring kelp forests have gone unnoticed or remained unconsolidated in reports on the causes of decline and assessments of individual projects.

More recently, heightened awareness and concerns about the growing threats and observed declines in kelp forests have motivated several papers in the scientific literature on recommendations for kelp forest restoration 2; 3; 4. The primary audience of these papers has been the scientific community, and valuable information about how to conduct restoration has not been easily accessible to multiple sectors of society. Further, the field of kelp restoration has lagged that of other marine ecosystems, with fewer projects and smaller attempts at restoration 5; 6; 7. As such, there is a compelling need to consolidate knowledge and establish guidelines for best practices for kelp forest restoration.

This guidebook, an initiative by The Nature Conservancy and the Kelp Forest Alliance (KFA) (kelpforestalliance.com), aims to distil lessons from past kelp restoration experiences around the world and to provide suggestions for how to manage and restore kelp forests. The work is informed by the authors and editors as well as by a global four-part series of workshops hosted in 2020. Because the field is rapidly evolving, the guidebook does not purport to contain all the answers but instead presents the best available information in an easily accessible format in hopes of advancing the field. We encourage users to be active participants of the KFA and to share their experiences and lessons learned at the KFA website.

In addition to the steps outlined in the following pages, we also provide a series of examples of restoration in practice that detail success stories, the challenges faced, and lessons learned in restoration.

1.1.1 Using the guidebook and target audience

This guidebook was developed for restoration project leaders and practitioners. The purpose of this guidebook is to assist users interested in restoring kelp forests by helping introduce and inform them of the various considerations, steps, and decisions required throughout the restoration process. Further, we provide detailed examples of restoration in practice (Fig. 1.1) to facilitate learning from previous restoration efforts. Users may consider each chapter individually depending on their needs or follow guidance from start to finish. Individual projects will always need to consider the local circumstances and ultimately ensure that the recommendations provided are appropriate for any specific project.

Further, a project database detailing ~200 recorded restoration projects is available at kelpforestalliance.com 8. Users may find this helpful to see what successful projects look like and find commonalities with their own projects. We also encourage users to upload their own projects and so contribute to advancing kelp forest restoration efforts.

Figure 1.1 Map of kelp restoration projects from around the world

1.2 Diversity and distribution of kelps

Kelp forests in the orders Laminariales and Fucales are marine ecosystems characterized by the presence of large brown seaweeds that form habitat over the seafloor 9. They can grow very fast and rapidly produce a vast amount of biomass 10;11 and create a three-dimensional structure that alters their surrounding physical environment 12; 13; 14. Therefore, kelp forests provide habitat, shelter, and food to many species 15; 16. Kelp forests dominate along approximately one-third of the world’s coastlines in polar/subpolar and temperate latitudes in both hemispheres (17; 18. Their diverse variety of habitat types delivers a broad range of valuable ecosystem services 19; 20; 21.

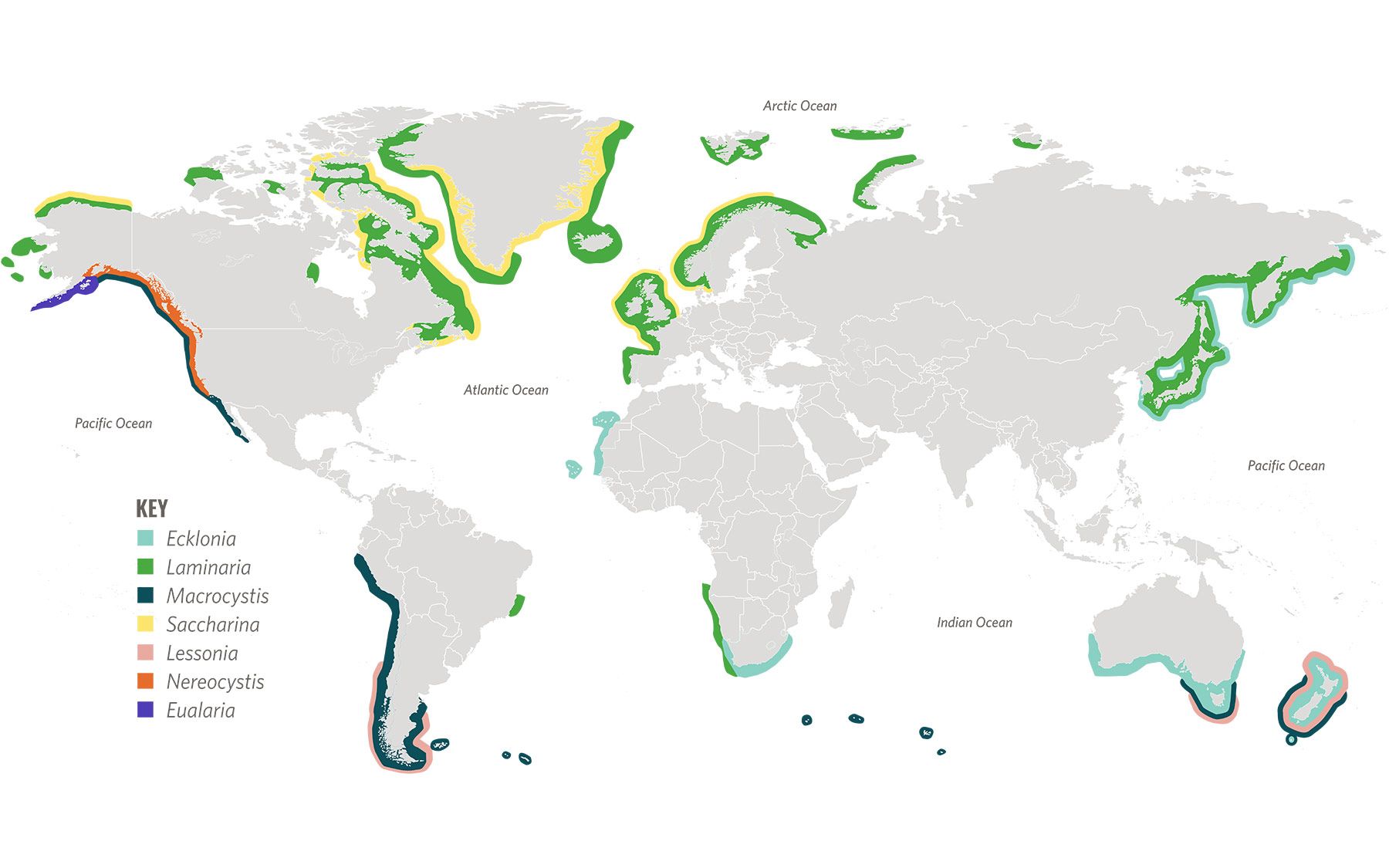

The orders Laminariales and Fucales encompass different species and functional groups across the globe 22; 23. Major genera within these groups include Macrocystis (North America, South America, Southern Australasia), Nereocystis (North America), Laminaria and Saccharina (Europe, Asia, and part of North America), Ecklonia (Asia, Southern Australasia, Southern Africa), Lessonia (South America, Southern Australasia), Sargassum (Pacific and Atlantic Ocean), Cystoseira (Mediterranean, Indian, and Pacific oceans), Fucus (Europe, Greenland, North America), and Phyllospora (Australia). Species in these orders comprise the three major functional groups: 1) Floating surface canopy forming species such as Macrocystis, Nereocystis, some Sargassum 2) Intertidal or subsurface stipitate kelps such as Ecklonia, Laminaria, and Saccharina, and 3) Low lying prostrate forms that occur in the subtidal (Phyllospora, some Sargassum) or intertidal (Fucus, Cystoseira). Species are either annual (e.g., Nereocystis) or perennial (e.g., Macrocystis) and can live up to 10 years or more (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Global distribution of kelp forests by genera

1.3 Decline of kelp forests

Kelp forests have declined around the world and in some cases have nearly disappeared entirely from a region 24; 25; 26; 27; 28; 29; 30. The cause of these declines range from local stressors, such as pollution, to global impacts, particularly climate change 31. Early declines of kelp forests in the 1800s have been linked to population expansion of sea urchins, most often facilitated by the removal of urchin predators from the ecosystem 32. Subsequent kelp population declines in the 20th century were driven by threats such as direct harvest of kelp or high levels of water pollution from urban areas 33; 34; 35; 36.

These stressors are still relevant to contemporary kelp ecosystem management but are now also combined with climate change, a phenomenon that has multiple consequences for kelp forests 37. Increasing water temperatures and marine heatwaves have resulted in large contractions of kelp populations as they are pushed past their physiological limit 38; 39; 40; 41. Warmer sea water temperatures have also facilitated the range expansion of herbivorous sea urchins, which can overgraze entire forests and create urchin barrens, a phenomenon identified in most countries that contain kelp across the world 42; 43; 44. More recently, temperature-driven shifts in the ranges of herbivorous fishes are also causing similar declines in kelp forests near the warm edge of their distribution45; 46. Such extensive losses have dramatic ecological and economic impacts. For instance, kelp losses have caused the closure of lobster, abalone, sea urchin, and kelp fisheries in several regions around the globe 47; 48;49.

1.4 The value of kelp and case for restoration

Kelp forests are integral to temperate and arctic seascapes and are linked to people and sustainable use of the ocean (Fig. 1.3). A global analysis of Laminaria, Ecklonia, Nereocystis, and Macrocystis species found that they generate > 100 thousand USD per hectare per year and billions of dollars annually 50. Because people can interact with kelp forests in so many ways, there are several reasons and motivations for wanting to restore and maintain healthy kelp forests. It is therefore important that the human element, outlined in chapter 3, is incorporated into any kelp forest restoration project plan. This incorporation can include working with communities to conduct restoration, ensuring that restoration meets the needs of the community, and integrating different knowledge sources into making decisions about kelp restoration.

Figure 1.3 Ecosystem diagram of kelp forests, including services; illustration by Jon Ferland

Human motivations for kelp forest restoration ultimately shape the goals for restoration and may be driven by market or non-market forces. Market driven motivations include the extraction and use of kelp itself 51 or the organisms supported by kelp forests such as fish and invertebrate fisheries 52, biopharmaceutical products 53, and the emerging markets for nutrient and carbon credits 54. Nonmarket motivations are human cultural, recreational, and educational experiences within a kelp forest. The specific motivations for a restoration project will shape the metrics used to measure its success (chapters 4 and 6).

1.5 Identifying patterns and causes of kelp decline

As predominantly temperate and polar/subpolar species, kelps grow best in cooler waters, and indeed temperature is often the best predictor of kelp distribution at large scales 55; 56; 57. Local factors that influence distribution include available nutrients and light for growth and photosynthesis, rocky substrate for attachment, wave exposure (high to low depending on the species), and the presence of grazers such as sea urchins or herbivorous fishes 58; 59; 60.

Persistent stressors pose perhaps the greatest challenges for kelp forest restoration. Stressors such as warm water events, sedimentation, and nutrient pollution must be mitigated before successful restoration can occur. Stressors like sedimentation and nutrient pollution are best managed from the source, and strict controls on water pollution are essential for kelp forest restoration (chapter 2, Sydney: Operation Crayweed). A combination of each or all these stressors can cause tipping points wherein kelp forests transform into urchin or turf barrens. Returning these barrens to kelp forests is difficult, as there is often a hysteresis effect wherein it is easier to shift to the barren state than to restore it back to the kelp state (i.e., lower levels of a stressor are required to recover than to tip the system; Box 2.3). As such, it is advised that, if possible, managers should look to prevent these shifts from occurring as opposed to reacting after the shift.

Because kelp forests can exhibit naturally high population fluctuations, it is important to determine whether an observed population decline is within the normal range of variation or indicative of an unusual event that requires intervention 61. Making this distinction is not an easy process and relies on detailed records of past kelp distribution and abundance. Such historical data also serves as a critical reference for establishing meaningful restoration targets and for determining whether restoration projects are successful in meeting their intended goals. The longer the time series of the historical data, the easier it is to determine if kelp restoration is needed (chapter 2).

Even in cases where restoration is desirable, it is still important to consider if it is wise. The local environmental conditions will inform whether restoration is feasible and therefore worthwhile to attempt. Feasibility often hinges on the initial cause of decline. Success is more likely to be achieved in situations where the cause can be mitigated (e.g., water pollution sedimentation) compared to those that have permanently shifted (e.g., above the species’ temperature tolerance) (chapters 2 and 7).

1.6 Using this guidebook and conducting restoration

Once you decide to get started with restoration, there are several considerations before you begin the restoration process (chapter 2). It is important to set clear goals and objectives that are informed by your motivations and objectives prior to starting any restoration project. Restoration is a social endeavour, and you must also consider how the social (chapter 3) and ecological elements of your ecosystem influence your project. These objectives will help inform your approach to restoration and ultimately inform whether you were successful in your attempt (chapter 4). Concurrently, you should establish where you would like to conduct restoration. Site selection can also be informed by both ecological and social circumstances (chapter 3 and 4). Sites may have special significance to the community and take precedence as a desired place to restore, or sites closer to existing kelp forests can provide a natural population source and enhance your restoration efforts (chapter 4.4).

Low-cost pilot projects can help you trial differing methods, test your assumptions, and evaluate sites for restoration before committing to large scale efforts (chapter 4.5). All projects must obtain the appropriate permits and consider the associated biosecurity risks (chapter 4.2). These steps are often lengthy and should be started early.

Naturally, you will need to consider how you are going to restore kelp to your area. It may be possible to restore kelp populations by simply removing the stressor (e.g., chapter 5.2 herbivores) or adding habitat (chapter 5.6) with no further intervention. If not, you will need a source population of kelp to restore to the environment (seeds or adults, chapter 5.3, appendix 1). Once you have your kelp stock, you will then decide if you are going to work to transplant kelps (chapter 5.5), seed (chapter 5.4), and if you will combine these efforts with grazer management (chapter 5.2) or added habitat (chapter 5.6). The cause of decline, availability of parent populations (natural or sourced—appendix 1), the technical ability of the restorationists, and the financial budget of the project will determine the appropriate methodology for your project. We explore these requirements and considerations in further detail in chapter 5.

You will need to monitor your site prior, during, and after restoration activity. This process will determine if restoration is needed, the impacts of your actions, and if you achieved your project goals. While often overlooked, this is a necessary step in any restoration project, and you should plan for it before work begins. We cover different approaches to monitoring and evaluations in chapter 6.

Global oceans are rapidly changing, and it may no longer be possible or advisable to restore the same species or population to an area where it once was. If you expect long-term changes, such as increased water temperatures in your restoration site, it is worth considering how you might restore today while planning for the future. We discuss available and emerging approaches to genetic selection, stress tolerant kelp, and “future proofing” in chapter 7.

1.7 Further reading

Wernberg, T., Krumhansl, K., Filbee-Dexter, K., & Pedersen, M. F. (2019). Status and trends for the world’s kelp forests. In World seas: An environmental evaluation (pp. 57-78). Academic Press.

Morris, R. L., Hale, R., Strain, E. M., Reeves, S. E., Vergés, A., Marzinelli, E. M., ... & Swearer, S. E. (2020). Key principles for managing recovery of kelp forests through restoration. BioScience, 70(8), 688-698.

Steneck, R. S., Graham, M. H., Bourque, B. J., Corbett, D., Erlandson, J. M., Estes, J. A., & Tegner, M. J. (2002). Kelp forest ecosystems: biodiversity, stability, resilience and future. Environmental conservation, 29(4), 436-459.

Eger, A., Marzinelli, E., Christie, H., Fujita, D., Hong, S., Kim, J. H., ... & Vergés, A. (2021). Global Kelp Forest Restoration: Past lessons, status, and future goals. ecoevorxiv.org/emaz2/