4.1 Key Takeaways

- Most countries need to significantly increase the amount of protected kelp forest habitat over the next six years to meet their 30x30 commitments to the Global Biodiversity Framework.

- Current data show that 16% of kelp forests are under some form of protection, but only 1.6% of kelp forests are in highly protected areas.

- Increasing the area of kelp protected should be achieved through a combination of highly protected areas, sustainably managed areas, and traditionally managed areas.

- 6.8% of areas are not classified in IUCN categories, and few MPA areas overall have been assessed to determine whether or not fishing is adequately managed. Addressing these gaps is a priority.

- Protection must balance the need to limit activities like fishing while sustaining local cultures and livelihoods.

4.2 MPAs and Kelp Forests

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are essential spatial management tools for supporting marine biodiversity by restricting human activities that impact marine life. As a result, the amount of the ocean protected has increased in the past decades. The level of protection varies by MPAs, with some fully restricting activities like fishing, while others allow limited and sustainable use. Although restricted and well-managed MPAs may be the greatest benefit for biodiversity1 and can provide opportunities for local stakeholders and rights holders, they can also create conflicts. Combining multiple forms of protection is crucial to conserve kelp forests effectively while also accommodating the rights and needs of Indigenous Peoples, local communities, and industries.

MPAs benefit kelp ecosystems by directly or indirectly protecting kelp populations, associated fish, invertebrates, birds, and marine mammals. Directly, they can regulate kelp harvesting and limit development, while indirectly, they protect species vital to kelp health. These include creatures such as predators of sea urchins, and the presence of these predators helps control urchin populations and promotes kelp growth2. Overall, MPAs have a positive impact on kelp populations, associated biodiversity, and can help maintain a diverse and healthy ecosystem.

4.3 Protection Classifications

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies MPAs into seven categories (Ia-VI) based on their protection levels:

- Ia (Strict Nature Reserve) : Areas strictly protected for biodiversity and research, with minimal human interference.

- Ib (Wilderness Area): Large, unmodified areas where human impact is minimal.

- II (National Park): Protected areas managed mainly for ecosystem protection and recreation.

- III (Natural Monument or Feature): Areas protected for specific natural features.

- IV (Habitat/Species Management Area): Areas actively managed to maintain, conserve, and restore specific species and habitats.

- V (Protected Landscape/Seascape): Areas where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced a distinct character with significant ecological, cultural, and scenic value.

- VI (Protected Area with Sustainable Use of Natural Resources): Areas that allow sustainable use of natural resources while ensuring long-term conservation.

Ideally, using a mix of management strategies allows for tailored conservation approaches that balance strict protection with sustainable use and the respect of different socio-cultural needs. For instance, strictly protected areas (Ia and Ib) can preserve critical habitats and biodiversity hotspots, while categories V and VI can support sustainable livelihoods and cultural practices.

Currently, 6.8% of established MPAs globally have not been classified into an IUCN category, and 86% of all MPAs have not been assessed to confirm if the MPA is truly effective in limiting fishing. Together, these gaps make it challenging to assess the effectiveness of MPAs in protecting kelp forest ecosystems. Ongoing efforts aim to improve the mapping and classification of these areas to better inform conservation strategies and policy decisions.

4.4 Total Kelp Protected

This report estimates the amount of Laminarian kelp forest protected by overlaying a published kelp forest biome3 with a map of marine protected areas categorised by the protection level of those MPAs4 (see section 8 for full methods).

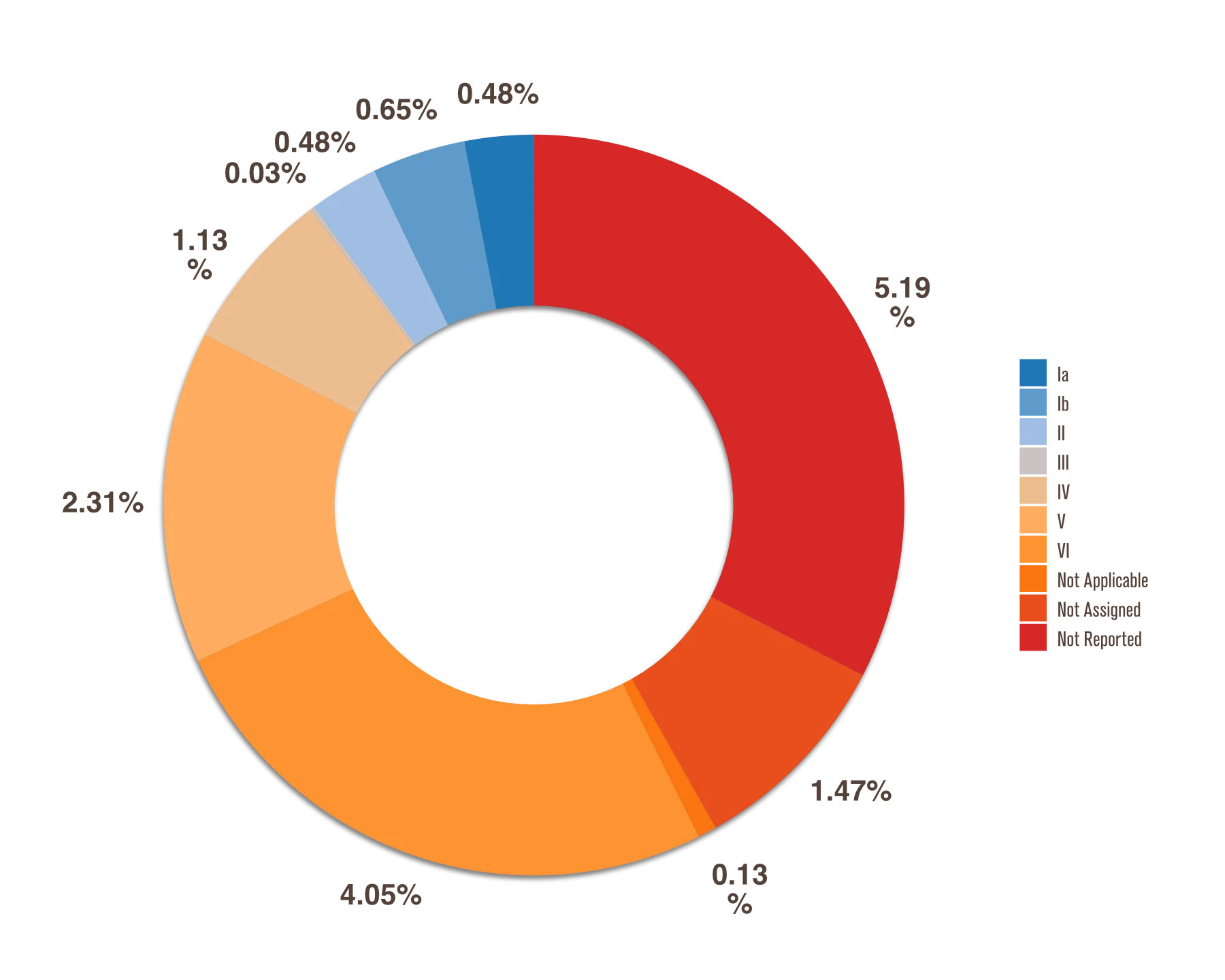

There is an estimated 15.9% of kelp forests in some form of protected area worldwide (Figure 4.1, as of January 2024). Only 1.6% of these areas are currently classified in IUCN protection categories Ia-III, the highest levels of protection. Approximately 4.2% of kelp is in the lowest form of protection (level VI). Further, a significant portion of kelp under protection is in areas not currently categorised (6.35%, not reported, not assigned, not applicable, Table 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Area Categories

Despite most countries not meeting the 30x30 targets, South Africa and some sub-national regions in the USA recently established a network of MPAs that currently protect more than 10% of their floating kelp forests5. These processes followed participatory approaches based on scientific guidelines.

4.5 Kelp Protected by Country

Only Japan has met their CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity) target of protecting 30% of their kelp forest habitat by 2030. Four additional countries (France, Norway, the United Kingdom, and Spain) have more than 30% of their kelp forests inside MPAs, although most of the kelp area in these countries is unclassified in the IUCN schema. Very few of the classified areas in these five countries are fully protected (Japan - 0%, France - 0%, United Kingdom - <0.1%, Norway - 3.94%, Spain - 0.24%). Given that well-managed MPAs are the most effective type of MPAs, these countries will need to consider increasing existing protection levels to effectively meet the 30x30 targets. Most countries assessed (14/25) have protected 10% or less of their kelp forest habitat. Except for Mexico (see section 8.1), no country has over 5% of its kelp habitat in a highly protected area (IUCN Classification Ia-III).

Protection of Fucoids in the Mediterranean

In the Mediterranean Sea, Fucoids (as opposed to Laminarians) from the groups Cystoseira sensu lato complex and Sargassum spp are the dominant kelp species, as well as the endemic Fucus virsoides. The Cystoseira s.l. complex is a key group recognised by the European Commission as a habitat of Community interest6. The proportion of Mediterranean fucoid forests under protection is currently unknown.

Across the region, as of 2020, 10% of the Mediterranean was classified under some form of protection. However, only 2.5% had a management plan, 1.25% was effectively managed, and 0.03% was in fully protected areas7.

There is, however, an important opportunity to enhance protection and restoration of fucoids following the adoption of the EU Nature Restoration Law in June 2024, which mandates the restoration of 20% of the EU's land and marine areas by 2030. This law emphasises, in particular, the urgency of marine forest restoration.

Deep Water Kelps

While kelp forests commonly live in shallow waters (< 25 m), there are several known deep-water kelp forests around the world. The conservation status of these populations is particularly difficult to assess, as we have poor maps of their current distribution and an even poorer understanding of their historic distribution. Deep water kelp populations include those in the Galapagos Islands (Ecklonia galapagensis), Brazil (Laminaria brasiliensis and Laminaria abyssalis), Madeira and the Azores (Laminaria ochroleuca), and the Mediterranean (Laminaria rodriguezii and Laminaria ochroleuca). A population of Ecklonia radiata in Oman has presumably gone extinct.

As these kelp forests become better mapped, they too will need to be included in conservation targets. Otherwise, they may be lost or threatened as a result of warming oceans or human activities such as trawling; the Mediterranean populations of deepwater Laminaria rodriguezii and L. ochroleuca have declined by 85% in the last 50 years due to trawling8.

Figure 4.2 Area Protected by Country