2.1 Key Takeaways

- Kelp forests provide a wide range of economic and cultural services to over 750 million people around the world.

- The potential economic value of ecosystem services in kelp forests is over $500 billion USD per year.

- Kelp forest fisheries (lobster, abalone, fish) generate tens of millions to billions of dollars for national economies each year.

- Nearly 800,000 tonnes of wild kelp are harvested each year.

- Kelp forests sequester ~32 million tonnes of CO2 annually.

2.2 Services Provided by Kelp Forests

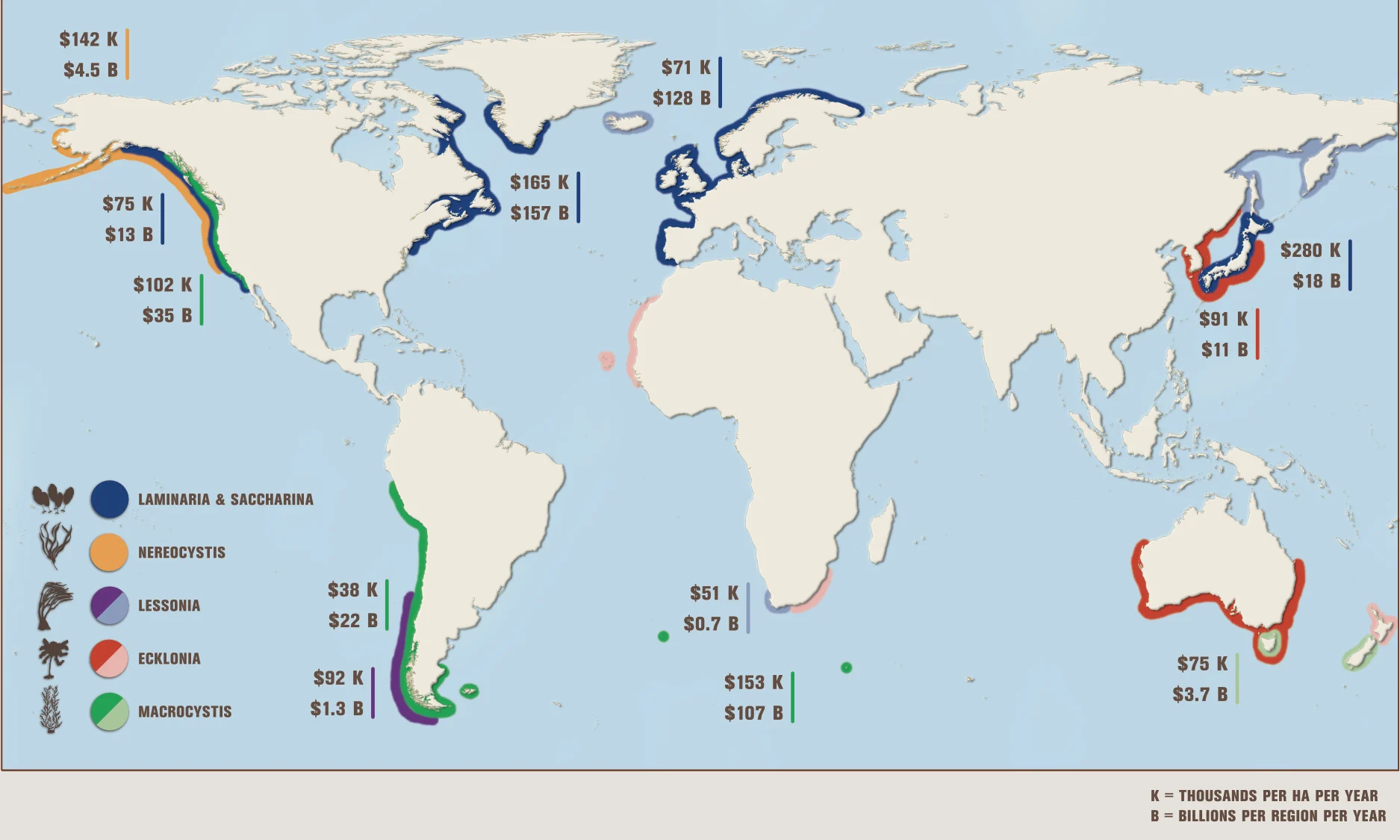

Kelp forests are foundation marine habitats that provide many different benefits to society. In economic terms, three key services are estimated at over 500 billion USD per year (Figure 2.1). These range from supporting fisheries to nutrient uptake to creating opportunities for recreation and spiritual fulfilment. As such, the value of kelp and what it can provide extends beyond the economic, but it is often helpful to communicate kelp’s contribution to economy. The total economic value1 of kelp forests’ services is presented below, though other methods may produce different values, e.g., welfare value.

Figure 2.1 Map of Ecosystem Services

2.3 Wild Harvest

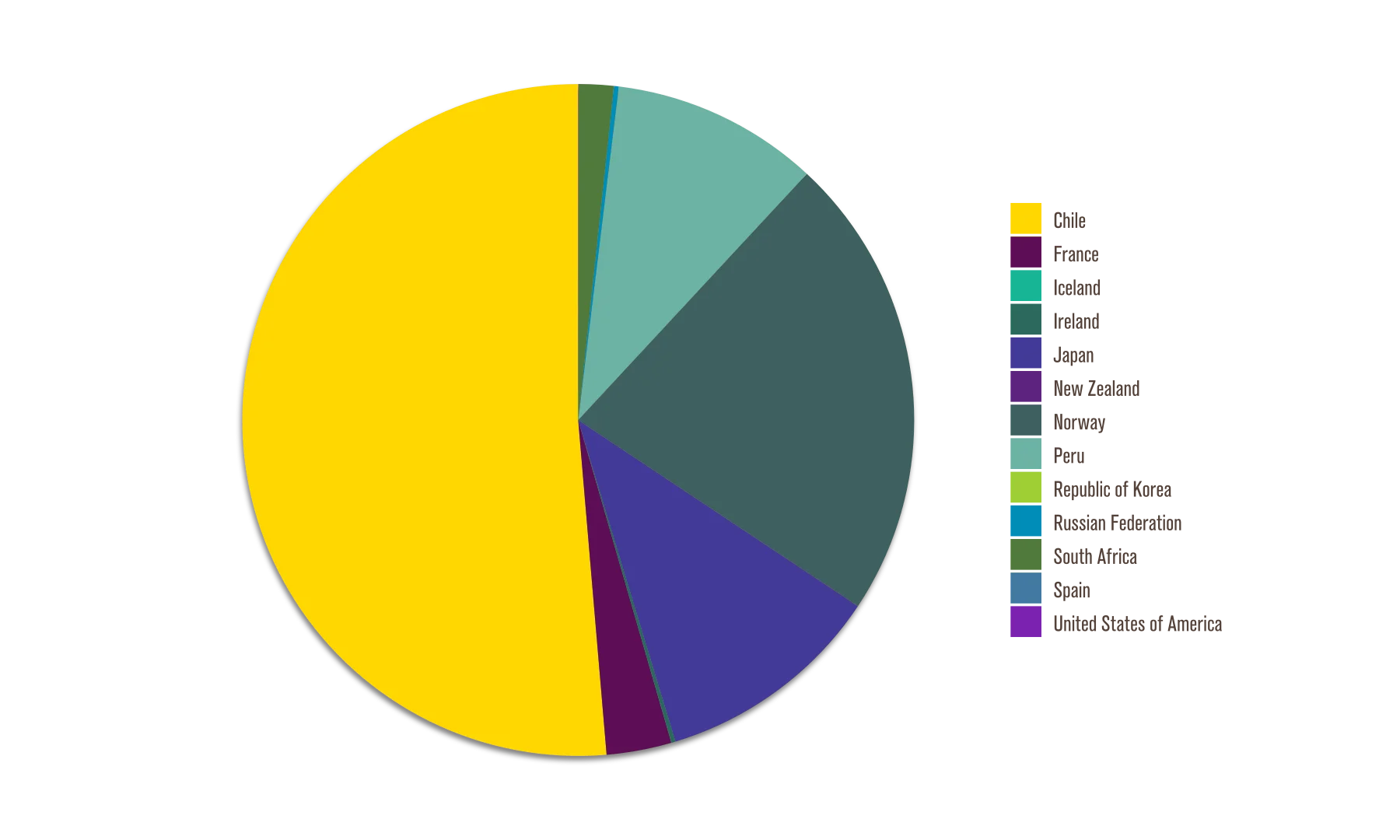

Kelp forests have directly supported coastal communities and provided food and materials to coastal communities for thousands of years. Here we define this direct provisioning from the sea as wild harvest. Across 14 countries, an estimated 600,000 tonnes of wild stocks are harvested annually (Figure 2.2). In the last five years, more than one million tonnes of wild kelp have been harvested in Chile, followed by Norway, Japan and Peru (477,352, 233,528 and 212,465 tonnes)2.

Figure 2.2 Wild Kelp Harvesting

2.4 Fisheries

Kelp forests are also critical habitats for many commercially and culturally important species, including abalone, lobsters, and fish; fish in particular being one of the major beneficiaries of kelp forests. It has been estimated that each hectare of kelp supports an average of 904 kg of harvested fish and seafood annually3.

Lobster and abalone are the most valuable fisheries in several countries. Approximately 3,060 tonnes of abalone and rock lobster are harvested annually in South Africa, with an estimated economic value of US$ 299.3 million per year. In total, 38 species with economic value linked to kelp forests are found in South Africa4. In Australia, approximately 9,199 tonnes of rock lobster and 3,614 tonnes of abalone are harvested annually, generating an estimated US$ 512.6 million per year5.

In addition, fisheries associated with kelp forests are also significant in other countries. In the USA, there are at least nine fisheries with economic value associated with kelp forests6. Seven fisheries in the UK are linked to kelp forests, with the rocky lobster fishery generating an estimated US$ 38.4 million per year7. In Spain, 32 species are fished in kelp forest areas, with an estimated annual revenue of approximately US$ 18 million8.

Table 2.1

| ECOSYSTEM SERVICE | KELP DESCRIPTION | KELP VALUE | SCALE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seaweed aquaculture | Kelp aquaculture is dependent on wild kelp forests for breeding stock | 17.48 M tonnes/yr | Global |

| Wild harvest | Kelp (Fucales/Laminariales) harvested in 2021 across 17 countries. | 0.77 M tonnes/yr11 | Global |

| Wild fisheries | Fisheries relevant biomass. Key fishery species such as lobster and abalone. | 2380 kg/ha/yr | Global |

| Nutrient absorption | Waste treatment/water purification, including nitrogen removal. | $17,608/ha/yr; Nitrogen removal - $73,800, 657 kg N/ha/yr12 | Australia, Global |

| Nutrient absorption | Kelp beds deplete nitrate and phosphorus concentrations but enhance ammonium and DOC. | £2400 M/yr | UK, Global |

| Wave dampening | The presence of kelp may significantly affect coastal stability during storm events (modelled study). | NA | Global |

| Wave dampening and Current Flow | Canopy kelp forests have limited, but measurable, capacity to enhance shoreline protection from nearshore waves. | NA | Global |

| Nursery Habitat | Kelp forests serve as important nursery habitats for ecologically and economically valuable fish (e.g., mackerel, cod, rockfish) and invertebrates (e.g., lobster, abalone). | NA | NA |

| pH regulation | The chemical environment within kelp forests positively impacts calcifying organisms, acting as refugia from ocean acidification. | NA | Global |

| Carbon cycle | Net primary production | 536 gC/m2/yr | Global |

| SCUBA/snorkel | Recreational divers interested in kelp monitoring and citizen science for purposes including exploration and absorption of wildlife, biodiversity, learning more about kelp ecology. | ~$197.2 M/yr | Global |

| Traditional Ecological Knowledge related to kelp | Kelp has been documented as a food source, recreational item, tool, and material used in art across multiple traditional and Indigenous cultures | NA | NA |

| Kelp ecology courses | Kelp holds high value as a source of scientific and applied research. Recreational divers interested in kelp monitoring and citizen science. | $25,957,253 | Chile |

| Kelp arts, movies, etc | Artistic practices involving kelp (sculpture/painting), photography, and shell-stringing culturally important necklaces from species found in seaweed. | NA | NA |

| Habitat | Loss of kelp reduces net primary production (NPP), detrital flow, mobile invertebrate populations, fish and sessile invertebrate richness, but it increases benthic light availability, sub-canopy algae species cover and richness, and sessile invertebrate cover. | NA | NA |

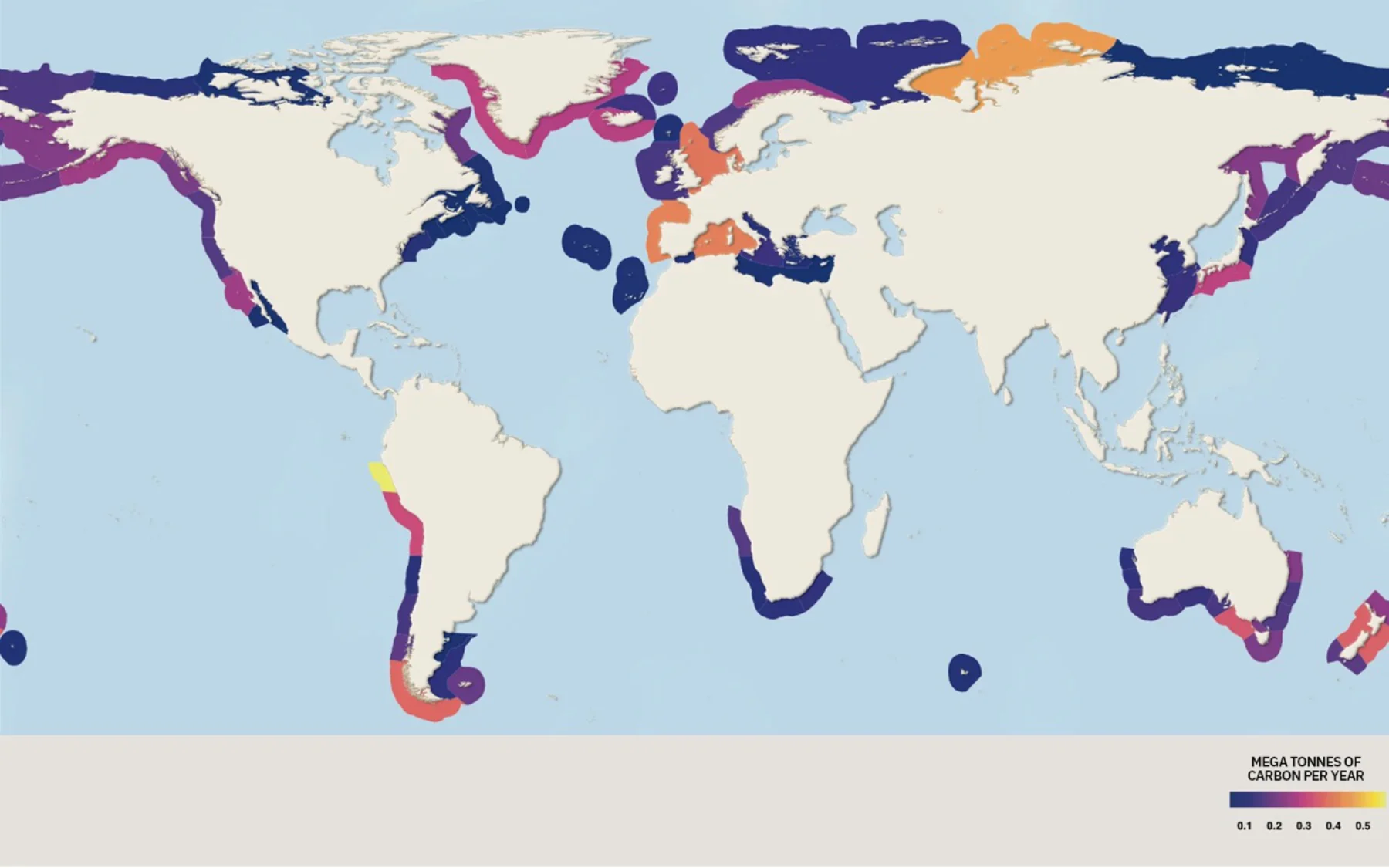

2.5 Carbon Removal

Kelps have very high carbon-fixation rates, an extensive distribution, and are increasingly being viewed as a tool for carbon dioxide removal to help mitigate climate change. Kelp forests were recently shown to transfer significant quantities of carbon to the deep ocean, where it can remain sequestered for >100 years9. These estimates suggest that a metre squared of kelp forest may sequester between 5 to 30 grams of carbon in the deep ocean every year. Globally, kelp forests are thought to sequester 8.6 million tonnes (range of 2.6 - 14.7) of carbon every year (32 million tonnes of CO2), with forests in Australia, the USA, New Zealand, Chile, and Peru having the greatest sequestration potential.

These estimates show that it is feasible—albeit technically complex—to link management actions such as protection and restoration to specific amounts of CO2 sequestered from the atmosphere. If done correctly, these methods can provide the basis for carbon credits in kelp forest ecosystems. It is important to stress that preventing the loss of kelp forests is the most cost-effective strategy to avoid losing their carbon removal capacity, as well as safeguarding the numerous other benefits they provide10.

Figure 2.3 Map of Carbon Sequestration