Photo Awards 2024 Finalists

Kelp Macro

Winner - Floral animal

Michael Sswat

Runner Up - Life Looks For Life

Eric Wahl

Second Runner Up - Otherworldly Oval-Anchored Stalked Jelly

Jackie Hildering

Horned Nudibranch

Kimberly Nesbitt

Nestled Flame

Grant Evans

Not Just A Fluke

Patrick Webster

Working On Pneu Material

Patrick Webster

Kelp at the End of the World

Cristian Lagger

Slug and Seaweed

Brian Skjerven

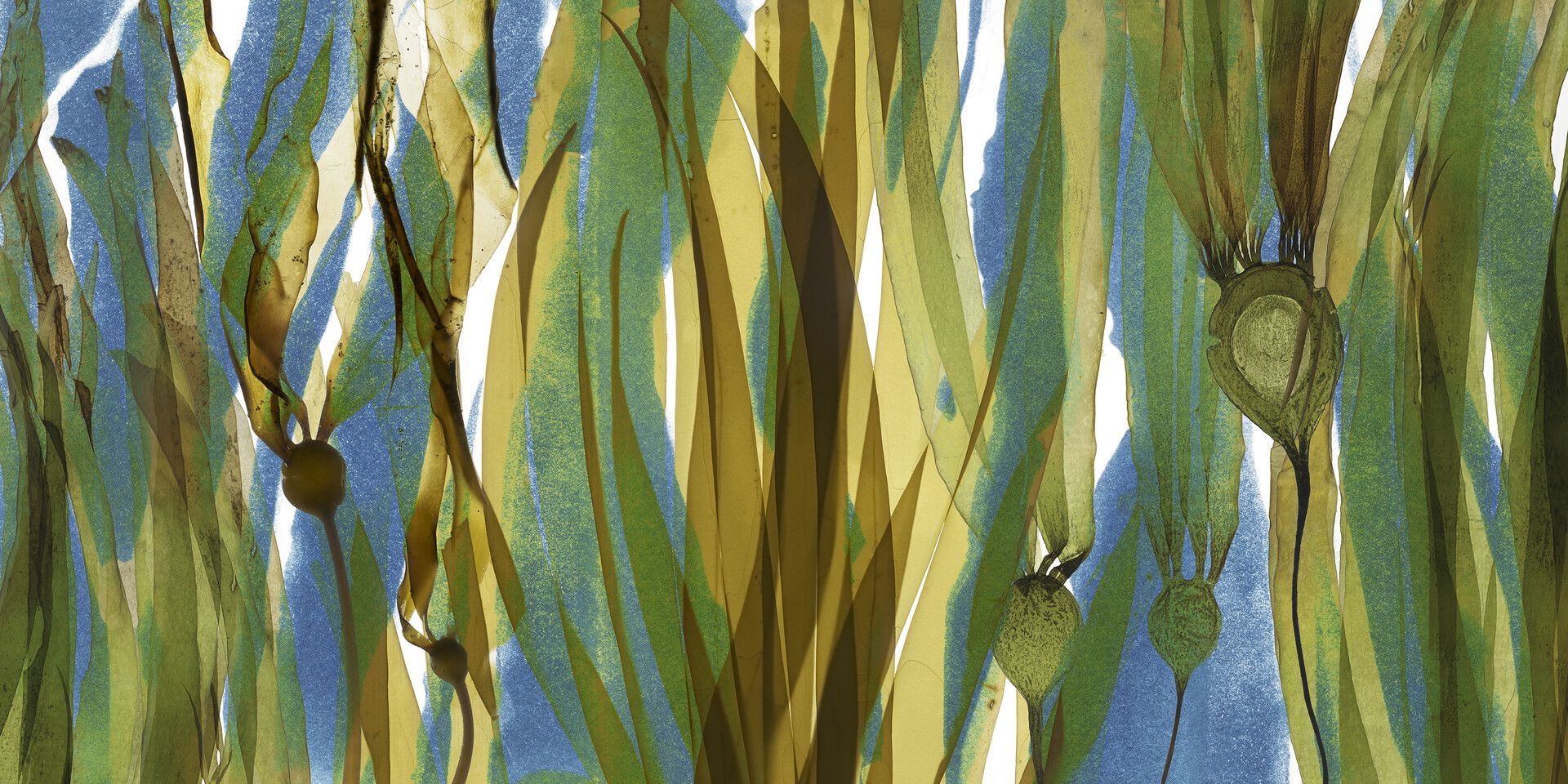

Sunlit Symphony: Colors of Kelp

Wanda von Bremen

Kelp Wildlife

Winner - Kelp Gunnel Portrait

Phillip Lemley

Runner Up - Canopy Hunter

Jon Anderson

Second Runner Up - Harbor Seal

Christine Dorrity

Busy Bird

Sage Ono

Kelp Forest Angel

Douglas Klug

Forest Brawl

Michelle Manson

Hanging Around

Michelle Manson

Envy

Amy Lawson

The Watchman of the Kelpforest

Gunnar Oberhösel

Pedal To The Nettle

Patrick Webster

Leopard Lurker

Helen Walne

JellyFish

Jellyfish

Get off my Turf!

Tim McClure

Connections to People

Winner - In The Shadow of the Canopy

Joseph Platko

Runner Up - Kelp Yourselves

Patrick Webster

Second Runner Up - Entangled

Wanda von Bremen

Coastal Forest

Nuno Vasco Rodrigues

Parting the Canopy

Oriana Poindexter

Into the Woods

Johnie Gall

Narnia: Diving into a Different World

Gunnar Oberhösel

Descending into the Forest

Jon Anderson

Chasing Kelp #2

Josie Iselin

Red Ab Workout

Patrick Webster

Kelp Ecosystems (Wide Angle)

Winner - Hooded Nudies

Brian Skjerven

Runner Up - Schooltime Blues

Sage Ono

Second Runner Up - Stars and Sunbeams

Jon Anderson

Summer Kelp

Xaime Beiro

Kelp Growth

Brandon Huelga

Kelp Glory

Christine Dorrity

Magnificence In The Water Woods

Patrick Webster

Red lipped gooseneck barnacles in kelp

Laura Tesler

Underglory

Patrick Webster

Crystal ball

Irene Middleton

Fantasia

Helen Walne

Canopeace Of Mind

Patrick Webster

Patagonian coasts

Joel Reyero

Liquid Gold

Joseph Platko

Great Southern Reef

Winner - Kelp Tentacles

Hunter Forbes

Runner Up - The final frontier

Scott Bennett

Second Runner Up - Golden dragon

Catherine Holmes

Tending the Octopus Garden

Hunter Forbes

Reflections

Amy Lawson

One With The Forest

Amy Lawson

Dragons Den

Amy Lawson

The Hypnotist

Francesca Page

In the winter months of South Australia, these waters host one of the world’s most unique and spectacular wildlife events. From May to August each year, more than 250,000 Giant Cuttlefish migrate to the cold and rocky waters here to mate and then die. I lay amongst the seaweed, surrounded by hundreds of Giant Cuttlefish battling It out for the females hiding below. I watch two males eyeing each other up, their male dominance and need to mate overpowering their senses. The start of elaborate colour and shape-shifting show paired with intimidating skin displays began in front of my very eyes. Let the Fight begin!

In the 90’s these incredible animals were nearly wiped out due to overfishing. In the space of 3 weeks, 38 boats caught 270 tonnes of Giant Cuttlefish. In the years following their population dwindled to next to nothing. But due to conservation pressures a permanent ban on fishing for Giant Cuttlefish has been put in place in this area allowing them to bounce back to healthy numbers. And now instead of fishing them, we dive with them to enjoy their beauty and wonder.

Hidden Dragon

Ian Segebarth

Golden Ray

Ian Segebarth

Kelp For Our Future

Winner - Urchin Undertakers

Sage Ono

Runner Up - Symbiosis

Giacomo d'Orlando

Second Runner Up - Lurking Urchin

Jon Anderson

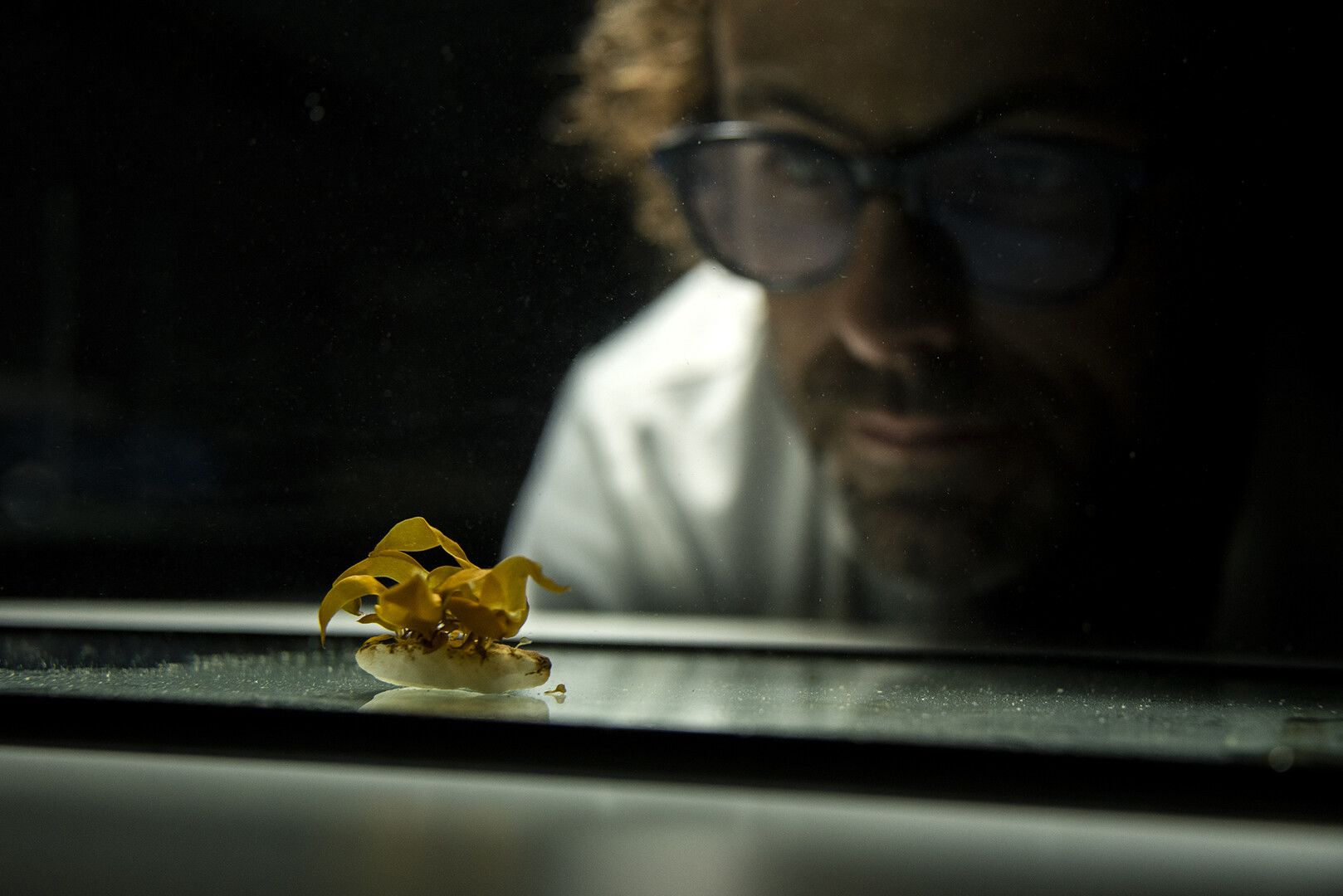

Self Seeding

Jarrod Borod

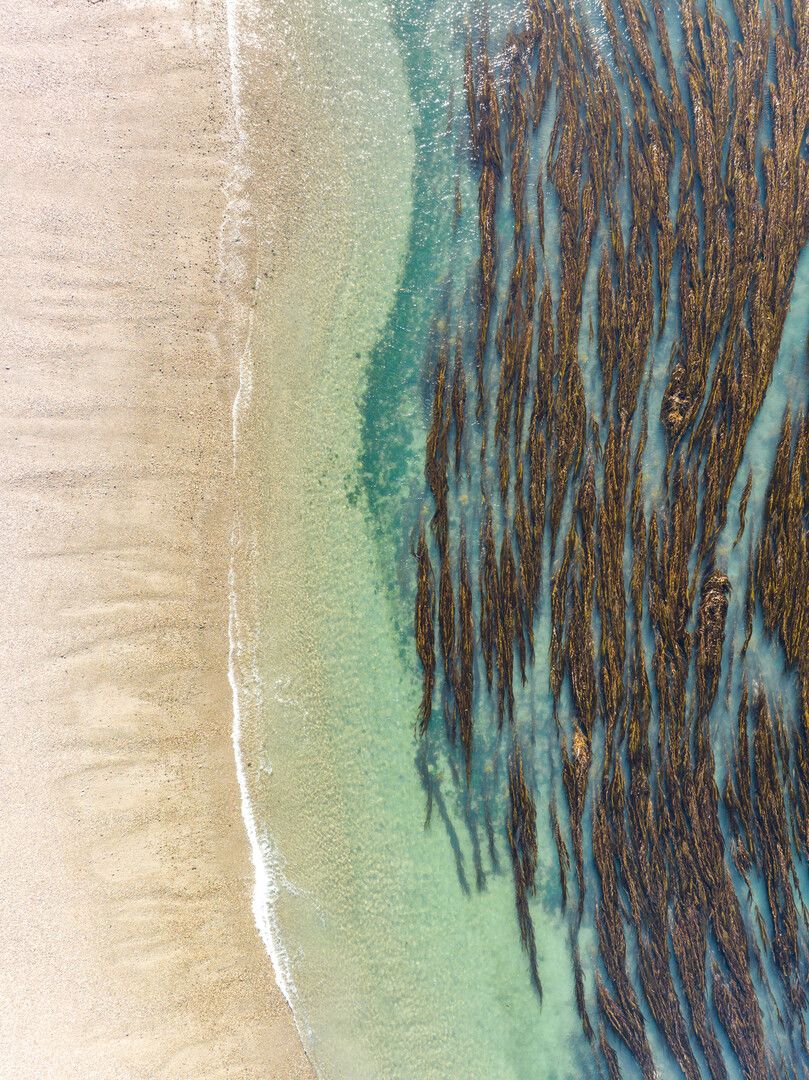

A signal of success: bull kelp restoration in northern California

Abbey Dias

Between Two Worlds

Luba Reshitnyk

Invasive Sargassum

Christine Dorrity

Blanket of Purple

Jon Anderson

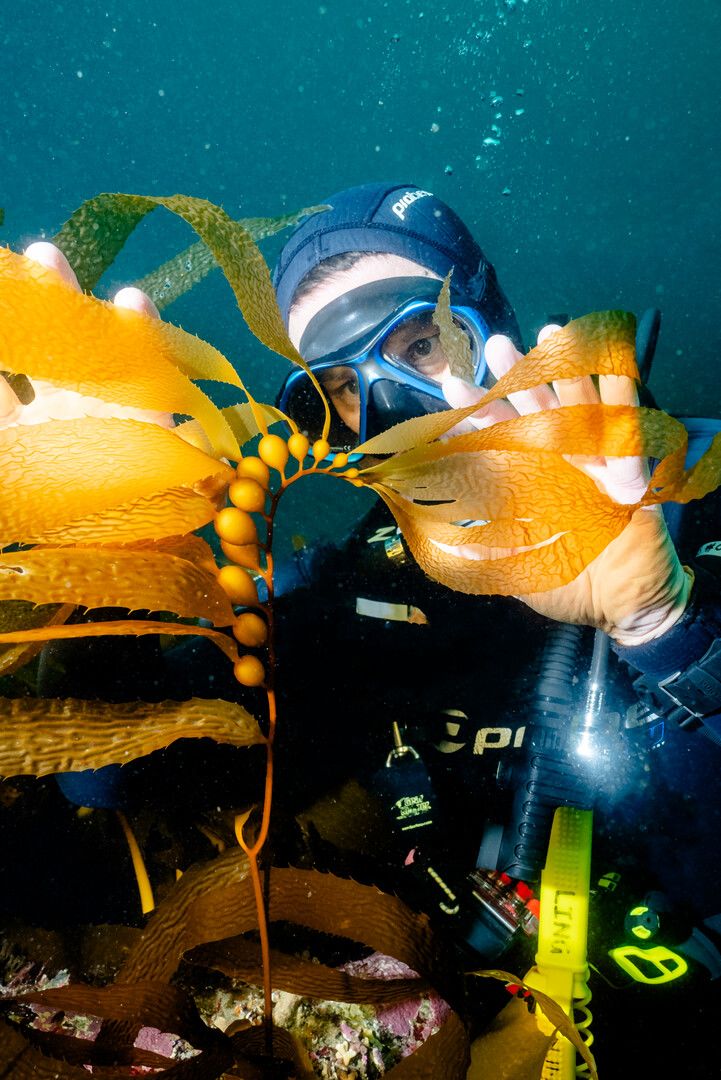

Bosques sumergidos del fin del mundo

Armando Vega

Extreme scientific expedition to investigate the carbon dioxide sequestration capacity of one of the southernmost kelp forests in the world: Peninsula Mitre, Argentina.

To connect kelp forests with people sensitively, the sportswoman and professional freediver Camila Jaber, together with the underwater photographer Laura Babahekian, created artistic expressions on these southern forests.

eKelp

Piotr Balazy

Stories from the Kelp

Winner - Of Blades & Spines

Kate Vylet

Driven by climate change, a cascading series of events have tipped the balance of California's kelp forests over the past decade. Warm water events weakened kelp growth and disease decimated sea star populations. Purple sea urchins, starved by the decline of their favored food source - drift kelp - and emboldened by the loss of their sea star predator, emerged from their crevices to seek algae. As they roamed across the reefscape, they grazed through an already depleted forest, diminishing it further. In some areas the kelp was all but lost, replaced by purple fields of spines known as urchin barrens - a stable but less diverse ecosystem.

Alarmed by the erosion of their local ecosystem, citizens, organizations, and governments banded together to find solutions for a changing kelp forest. Their approaches and efforts vary, but they're united in their resolve to save the kelp forest they love.

Despite the dire circumstances, in some regions the kelp has stood against these environmental stressors. In central California, patches of forest have held strong even as they are interlaced with barren. And recent years of cold upwellings have supported an annual resurgence of young kelp, reinforcing these remaining strongholds in a new equilibrium.

Through everything, the native purple urchin has been vilified for its conspicuous role in the loss of kelp. But, like the kelp itself, the urchin belongs to the underwater forest and plays an essential role in this vibrant ecosystem. Ultimately the imbalance taking place is steered by the intangible forces of climate change - a shift both kelp and urchin are struggling to survive.

But if the forest has taught us anything, it's that nature is resilient. And in its resilience is a message of hope.

Runner Up - A Kelp Story

Sage Ono

Kelp Restoration through Urchin Harvest

Matt Testoni

Stories from the Forest

Nuno Vasco Rodrigues

Kelp Farming in Southeast Alaska

Kimberly Nesbitt

The Iridescent Ones: Abalone Restoration on the US Pacific Coast

Oriana Poindexter

Purple Urchin Imbalance

Jon Anderson

Bull Kelp Life Story

Josie Iselin

Ocean Reforestation: Crayweed Revival

Tom Burd

Crayweed, (Phyllospora comosa) is believed to have formed thick forests throughout Sydney’s coastal waters, as it naturally does along other parts of the NSW coastline. However, in the 1980s it largely disappeared without any documentation, likely due to high water pollution and untreated sewage outflow.

“Operation Crayweed” was formed to reverse this trend and is now a flagship project at the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, in collaboration with UNSW and the University of Sydney. Excitingly, the restoration works involve the local community in a collaborative effort to reintroduce this vibrant seaweed to Sydney's picturesque coastline.

Kelp: We Need These Algae

Patrick Webster